PEI and Cystic Fibrosis

About

Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive genetic disease which causes faulty chloride and bicarbonate secretion in epithelial cells in many parts of the body. This affects the water content of epithelial cells, giving rise to many clinical symptoms including progressive damage to the respiratory and digestive system. In the pancreas, secretions become viscous with a high salt content1 which together with thick mucus blocks the release of enzymes, causing pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI).1,2 Although treatment for cystic fibrosis in recent years has extended life expectancy, patients still suffer a premature death.1

Epidemiology

Cystic fibrosis affects up to 1 in 2,500-3,000 live births,1 and most people with the condition in the UK will be identified through the newborn cystic fibrosis screening programme.3

PEI is present to some degree in 55-100% of cystic fibrosis patients,2 with 85-95% of children showing symptoms at one year of age. The prevalence of severe PEI has been reported in more than 80% of people with cystic fibrosis.2

Causes

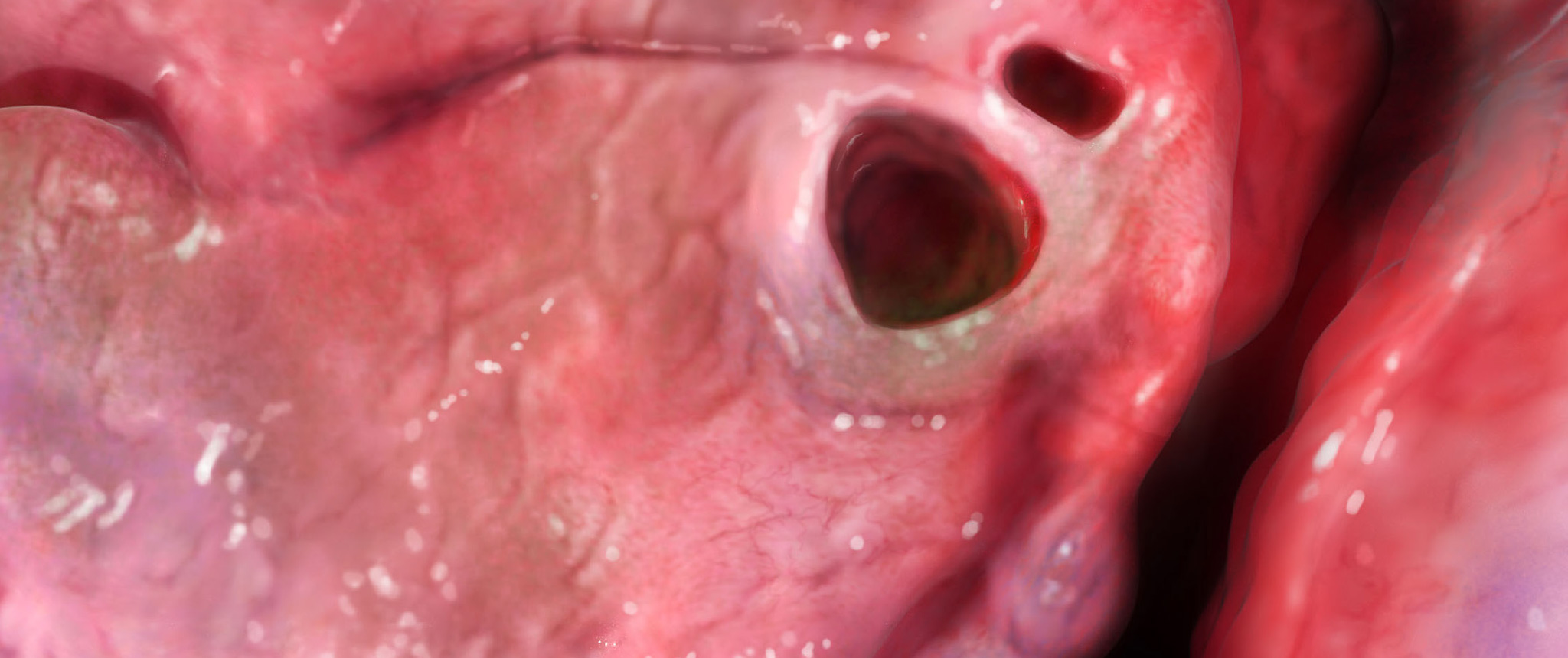

PEI in cystic fibrosis results from the presence of highly concentrated, thick pancreatic secretions which obstruct the pancreatic ducts. The consequent reductions in the volume and concentration of pancreatic enzymes and bicarbonate reaching the gut result in fat and protein maldigestion and malabsorption. These are exacerbated by impaired gastrointestinal motility and increased gastric acid secretion. In addition, bicarbonate secretion from the pancreas is reduced which can cause delayed gastric emptying and gastro-oesophageal reflux.3

Furthermore, the persistence of highly concentrated enzymes with the acinar and ductile structures results in local cellular damage, acinar atrophy, fibrosis and fatty replacement of normal organ structures. 3

Pathophysiology

Cystic Fibrosis is caused by mutations in the gene coding for the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein. As a result of these mutations, there is functional loss of the CFTR protein which decreases secretion of chloride at the apical surface of epithelial cells and increases re-absorption of sodium and water across these cell surfaces.1,3

Impairment of cellular chloride ion transport affects intracellular water levels and has the effect of reducing the volume and increasing the viscosity of the exocrine secretions of the pancreas. This leads to obstruction of the pancreatic ducts, acinar cell destruction, fibrosis and PEI.3

The presence of thick, high-salt fluids occurs in many organs as well as the pancreas, including the lungs, giving the other classic cystic fibrosis symptoms of recurrent respiratory infection with bronchiectasis.1

The chance of developing PEI in patients with cystic fibrosis depends on the gene mutations they carry. In general, the vast majority have two ‘severe’ gene mutations and so develop PEI. About 10% of cystic fibrosis patients carry at least one ‘mild’ mutation and usually do not show symptoms of PEI (they remain pancreatic sufficient) and grow normally, although they may develop PEI in adult life.2

FACT

PERT significantly improves nutrient digestion and absorption but despite PERT, 19% of children with PEI due to cystic fibrosis in the UK are below the lOth percentile for weight, possibly because of alterations in gastrointestinal pH, motility, and transit which impair nutrient absorption.

Imrie, et al. 20103; Keller & Layer, 20052

Signs and Symptoms

In general, PEI causes malabsorption and maldigestion, resulting in symptoms of:1,4

Symptoms

- WEIGHT LOSS

- ABDOMINAL PAIN

- FATIGUE

- DIARRHOEA

- STEATORRHOEA

- FLATULENCE

For some infants with cystic fibrosis the amylase and lipases in maternal breast milk may compensate for PEI to some degree, so may not show weight loss until after they are weaned. Older children may compensate for loss of nutrients in the stools by increased appetite and food intake, only presenting with sudden weight loss after intercurrent infections during which feeding has decreased.3

A small proportion of patients with cystic fibrosis (<10-20%) who are homozygous or heterozygous for the less severe mutations may have enough pancreatic function to grow normally throughout childhood. Such patients may develop the symptoms of PEI during adulthood, along with bouts of pancreatitis.3

Steatorrhoea is characterized by foul-smelling, greasy stools, and is usually the most classical clinical manifestation of PEI.5 Steatorrhoea may be associated with deficiencies of fat soluble vitamins: A, D, E and K, leading to osteoporosis and other complications.2

Complications

Complications from maldigestion and malabsorption may have a progressive and detrimental effect on a patient’s wellbeing and increase morbidity and mortality. 4,6,7 For further information on the complications of PEI,CLICK HERE.

Diagnosis

There are several methods available for diagnosing PEI, with the indirect methods being the most frequently used in the clinical setting. Of these, the 3-5 day faecal fat balance test is recommended because it has been shown to correlate well with direct tests of pancreatic function. However the faecal elastase is a practical alternative.1

For a detailed discussion of these techniques, CLICK HERE.

For infants diagnosed with cystic fibrosis, weight and height should be measured every month, and for children every 2-3 months. An indirect test for PEI should be carried out every 4-6 months.

The frequency of these tests should be increased if patients with cystic fibrosis are not achieving expected weight gain or develop symptoms associated with PEI such as steatorrhoea.1

| Measurement | Infants (0-2 years) | Children (2-18 years) | Adults (>18 years) |

| Height (supine/length) | 1-2 weekly until thriving, then monthly | – | – |

| Height (standing) | – | 3 monthly | Annually† |

| Weight | 1-2 weekly until thriving, then monthly | Every clinic visit* | Every clinic visit* |

| Head circumference | 1-2 weekly until thriving, then monthly | – | – |

| Plot on appropriate growth chart | ✔ | ✔ | – |

| % IBW | ✔ | ✔ | – |

| BMI | – | ✔ | ✔ |

| Plot on BMI centile chart | – | ✔ | – |

Adapted from Stapleton, et al. 2006.1

* Fortnightly if clinic visits are more frequent than this.

† If growth has ceased; otherwise 3 monthly until cessation of growth is demonstrated (consider that growth may continue up to 20 years in males with CF).

% IBW: percentage ideal body weight, BMI: body mass index.

Adapted from APC Guidelines, 2015.1

Treatment

Treatment of PEI in patients with Cystic fibrosis

Failure to treat PEI in patients with cystic fibrosis can result in:3

- Stunted growth

- Delayed puberty

- Deteriorating lung function

- Respiratory failure

- Early death

Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) is essential in patients with PEl due to cystic fibrosis in order to correct malabsorption and malnutrition, reduce steatorrhoea, and achieve normal growth.3

PERT doses needed in cystic fibrosis patients can vary between individuals. For infants, initially 5,000 lipase units should be taken with each feed or meal. For children and adults, begin with 500 units of lipase units/ kg body weight per meal. Dose increases, if required, should be added slowly, with careful monitoring of response and symptoms. 8,9

Fibrosing colonopathy has been reported in patients with cystic fibrosis taking in excess of 10,000 units of lipase per kilogram body weight per day. 8,9

For children of school age, taking large numbers of capsules with food may cause stigmatization, which can lead to poor adherence and consequently poor growth and/or weight loss. The consequences of suboptimal PERT management should be discussed with patients and their families.3

Doses can be titrated based on weight gain and bowel signs to find the lowest effective dose. Signs and symptoms of malabsorption such as pain, excessive gas, frequency and stool consistency are not indications for dose adjustments.1

In addition to PERT, fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K should be supplemented prophylactically.1

To learn more about the treatment of PEI with PERT, dosing of PERT, and other aspects of PEI management, CLICK HERE.

Long-term management and monitoring for PEI in patients with cystic fibrosis1

Children should be assessed at regular intervals for height, weight and head circumference, dietary intake, biochemical assessments and a review of bowel habit and function. In very young children, dietary intake assessments should be more frequent.

Adults may lose height over time due to ageing, osteoporosis or kyphosis. A thorough assessment of dietary intake should be conducted at least once a year.

Key areas of nutritional assessment for cystic fibrosis patients:

| Key areas of assessment | Purpose |

| Energy intake | Energy balance and affect on weight |

| Fat intake | Energy density and PERT adequacy |

| Food preferences and variety | Adequacy of micronutrient intake Fibre intake Target areas for change |

| PERT: dosage, adherence and gastrointestinal symptoms | Adequacy of PERT regimen |

| Supplements: vitamins and minerals, oral and enteral nutritional supplements | Adequacy of micronutrient intake Contribution to energy and nutrient intakes |

| Sodium and fluid intake | Hydration and sodium status |

| Nutrition-related complementary or alternative therapies | Adequacy of micro and macronutrient intake |

References

- Smith RC, Smith SF, Wilson J, Pearce C, Wray N, Vo R, et al. Australasian guidelines for the management of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. Australasian Pancreatic Club, October 2015. pp 1-122.

- Keller J, Layer P. Human pancreatic exocrine response to nutrients in health and disease. Gut. 2005;54(Suppl 6):vi1-28.

- Imrie CW, Connett G, Hall RI, et al. Review article: enzyme supplementation in cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic and periampullary cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(Suppl 1):1-25.

- Sikkens EC, Cahen DL, van Eijck C, Kuipers EJ, Bruno MJ. Patients with exocrine insufficiency due to chronic pancreatitis are undertreated: a Dutch national survey. Pancreatology. 2012;12(1):71-73.

- Domínguez-Muñoz JE. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency: diagnosis and treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(Suppl 2):12- 16.

- Ockenga J. Importance of nutritional management in diseases with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11(Suppl 3):11-15.

- Fitzsimmons D, Kahl S, Butturini G, van Wyk M, Bornman P, Bassi C, Malfertheiner P, George SL, Johnson CD. Symptoms and quality of life in chronic pancreatitis assessed by structured interview and the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-PAN26. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(4):918-926.

- Creon Micro Summary of Product Characteristics. Availavle from : https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5564 Last acessed November 2017

- Creon 10,000 Cpasules, Summary of Product Characteristics. Available from : https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1167 Last